In loneliness, it was almost always frozen. The prisoners wrapped themselves in sheets and extra clothes, and went back and forth to keep them warm. One day I was able to see my breath.

I was silenced, but some prisoners began to tear the blankets, stuff the toilets and wash them, and flooding the unit.

One night, the prisoners at the top of the unit began to “flood” together. The dirty water plunged from the upper floor to the lower level, and cells flooded there. My cells are filled with water to my knees. After that, as the pipes were clogged, the toilets, including mine, started to get flooded, adding to the confusion. Fearful, I flew to the bed, but began to rise until the dirty water wrapped around the edge of the mattress.

I cried out to help the officers, but no one came. After a while the water stopped rising and began to retreat, but the damage took place – my cells were filthy. An hour or two later, the officer came and I begged him to open the door.

He smiled. “It’s the third shift” – which means the unit had to remain locked up – “I haven’t opened the door.”

“It’s awkward here, buddy. At least let me get some water out,” I begged.

“You’re fine,” he said before leaving.

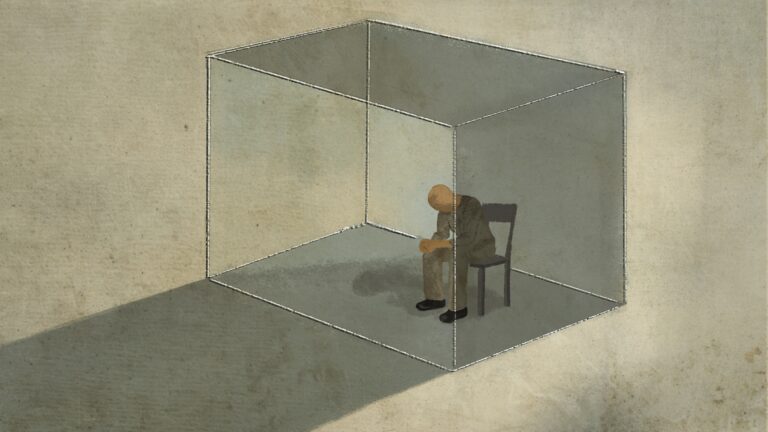

There was shit all over the floor. I felt like an animal in a cage.

“No, it’s not again.”

My trial began in December 2004 and continued until the conviction in April 2005. They were quarantined until they were sent to the NJSP in August 2005. It was two years of solitary confinement.

In the NJSP, they were immediately placed in the General Population Unit. I was now able to go to the Confusion Hall to eat three times a day, access religious services, and post work details in the kitchen, laundry or other areas of the prison. We went to the garden and the gym and had regular visitors.

I’ve learned that the only way you’re isolated is to get into trouble. So I made it my business to avoid anything.

But 17 years later, I ended up locking up because I had a rogue USB wire. I was sent to a “temporary” retention cell for a prison-related violation. The above layers were prisoners spending their time at ADSEG. Unlike the lockups of county jails, this place had big ears – the ears were terrible and loud.

Some prisoners had cursed each other. Others were cursing the inmates and the police officers who were screaming. And then there was a door banger that kicked the metal doors of a donkey-like cell. It was a zoo.

The previous resident was clearly in the way. The mattress was in ruins. There was a decomposed food. A dry pile of shit sat in a stainless steel toilet.

Still, I wasn’t a fresh newcomer anymore. I was now a middle-aged man with nearly 20 years of experience in one of the most infamous prisons in the country.

I gathered my strength, joined the prisoner’s chorus, asking for some cleaning supplies and “night bags” and “night bags” with “toothpaste, toothbrushes, clothes, toilet paper, spoons, cups, bed sheets, blankets, etc.”

“What do you want?” asked me a young overworked officer.

I pointed to the toilet shit. He simply shrugged and told him to clean it with water from the sink.

“Why am I supposed to clean it with?” I asked, upset.

“Use your hand,” he said, leaving.

It took 20 years of patience and self-control to hold onto the rise of anger.

For the next two days, I adjusted my pace.

It was the third night I heard the child next to me starting to wash away. I knew what was coming, but there were no blankets or sheets to block the door. The dirty water began to pour into my cells. As the water level continued to rise, I jumped onto the metal bed, praying that the toilets wouldn’t start to overflow. “Please, no, never again,” I begged.