The super-powerful human science fiction trope with computer and bionic implants is rapidly becoming a reality, and today startups hoping for a role in how it unfolds have announced some funding.

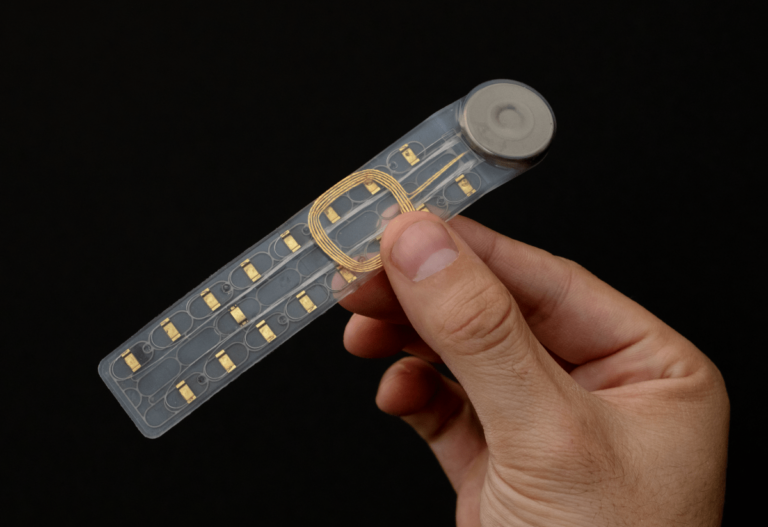

Phantom Neuro is developing a wristband-like device embedded under the skin so that a person can control the prosthetic leg, raising $19 million to fund the next stage of development.

Startups have already hit several important milestones for medical technology startups. I received two FDA designations. One is a groundbreaking device for taps. The latter is selective and is published through the institution’s medical device accelerator program designed to streamline Phantom’s “path to commercialization.”

The company also has some operational victory. The technology is built on the concept of phantom limbs. The amputee still feels that there are physical limbs due to the nerve endings that were connected to the limb.

Phantom claims that its “Phantom X” software can “read” these nerve impulses and convert them into attached prosthetic movements, showing 94% accuracy with 11 hand and wrist movements in a recent non-invasive “elevation” study. Phantom says that when the strip is embedded under the skin, it becomes even more accurate. The company claims that users can restore 85% of their features with just 10 minutes of calibration.

Ottobock, a German manufacturer of prosthetics and other medical devices, leads the round as a strategic advocate. It also featured the company’s previous investor breakout venture, Draper Associates, Lionbird Venture, Time Bio Venture, Risk and Return (aka Rsquared), as well as the real VCs of new investors, Metis Innovation, E1 Venture, Jump Space, Mainsheet Venture and Brown Advisory. Other startup investors include Johns Hopkins and Intel.

Phantom has raised $28 million so far and has not disclosed its valuation.

From stress fractures to scaled impact

Based in Austin, Texas, the Phantom was the creator of Dr. Connorgrass. Dr. Connorgrass is a polymas big thinker type who broadens his eyes when he talks about his vision for the past and the future.

Growing up in Oklahoma, Glass said he had a strong purpose from an early stage. His plan, he said, was to join the military when he grew up “to have a reduced impact on the world.”

As a university student, it took the form of participating in ROTC, where he discovered a harsh reality. He had a tendency to get repeated stress fractures. It would ultimately limit what he wants to do in the military, he realized.

Looking back at his experiences in his youth, we observed brain surgery (his dad was friends with a neurosurgeon, and apparently he was allowed to sit on or…), Glass had a “a-ha!” Instantly, I created a pivot.

He dropped his political science major and went out in advance instead. He decided that his scaled impact would be to become a neurosurgeon and help people with limb problems that are even more severe than just repeated stress fractures.

Glass eventually graduated from Oklahoma Medical School and was inspired by science fiction, YouTube and real-life scientific research, but landed in Johns Hopkins and conducted cutting-edge medical research in the field of brain implants used to control physical movements.

There he had another inspiration. He saw that in addition to being very invasive, the brain implant field was still largely early, cumbersome and inaccurate.

“A team of doctoral students are running around desperately, putting things on computers and typing,” he said of the typical environment in those labs. “There’s a huge cable that requires sticking to the implant that comes out of the patient’s skull. This allowed the signal to get out of the implant and go to the limbs. This was struck by the fact that this is not scalable at all. This is purely conceptual evidence.”

His focus has shifted once again to looking at the wider neural networks in the body, still focusing on “sweep impact” and scale. This led him to focus on the end of the nerves, the concept of phantom limbs, and how to bring these into the physical world by understanding what those nerves are trying to inform. That’s why Phantom Neuro was born.

If you are wondering whether plastic strips can be planted in the limbs to make the prosthetic easier to control, then it is not an area that is completely unstretched. There are already treatments for placing implants in the spinal cord, birth control, breast enhancement, and treatment procedures to monitor heart activity. Phantom Neuro believes this is just another step in its trajectory and hopes the market will look like that.

The company plans to make technology available first for prosthetic weapons and then add foot support. Technology applications go beyond amputees. Because it could also be used to control robots remotely, and because we live in the age of AI training, we could use that data to help robots learn to move in more human-like ways. But it’s all very important in the distant future.

Phantom focuses on building neural interfaces and technology, so there is an obvious handoff that requires equally impressive R&D in the form of “edge devices.” Glass said Phantom is about working with many companies’ products, but joining Ottobock, one of these large developers, is clearly a sensible move to get closer to its development.

“I think Phantom has made good progress in the nerve interface between the prosthesis and the human body,” said Dr. Arne Kreitz, Ottobok’s CFO. “That’s why we invested. It’s an interesting approach and not very invasive. There’s a lot going on right now from the brain interface and the less invasive methods.”