The general fusion was fired last week at least 25% of employees just days after hitting a key milestone for the latest fusion demonstration devices.

CEO Greg Twinney posted an open letter on the company’s website on Monday. The new LM26 device was something needed for the fusion conditions – the general fusion was lacking in money, allowing the plasma to be compressed. He writes: “(T)Oday’s funding environment is more challenging than ever, as investors and governments navigate the rapidly changing and uncertain political and market environment.”

The 23-year-old company, which many still describe as a startup, is a major Canadian participant in the commercial fusion power race. It raised $440 million, including a $22.66 million round that closed in July, according to Pitchbook. Supporters include Jeff Bezos, Temasek and BDC Capital. However, the money was not enough to show that a unique approach to fusion could be put into practice.

The typical fusion light form highlights the challenges facing the fusion industry.

To date, only one device has been able to hit the so-called scientific break-even point. To hit a commercial break-even point, a nuclear reactor must produce several dozen times more energy than has been proven.

The road to these milestones has proven to be extremely expensive. The general fusion tally may seem impressive, but it’s in the middle of the pack. Commonwealth Fusion Systems raised over $2 billion, Helion attracted more than $1 billion, and Pacific Fusion startup pledged $900 million in Series A alone.

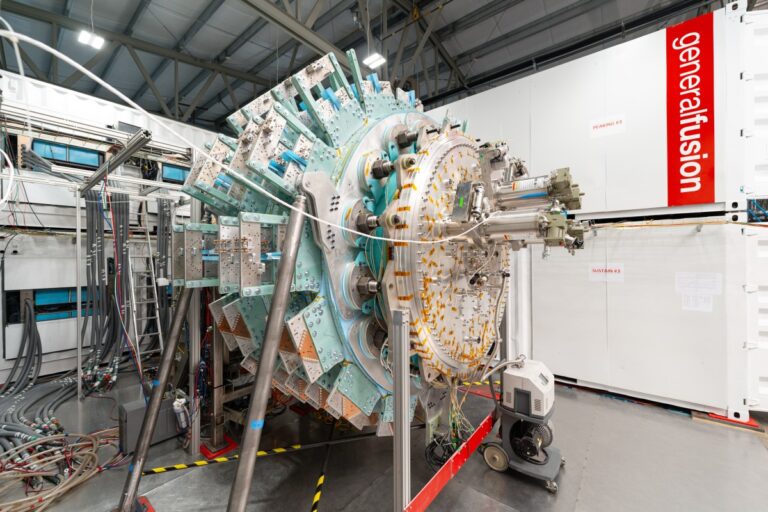

Part of the challenge with General Fusion is that it takes a different approach than many of its competitors.

TechCrunch Events

Berkeley, California

|

June 5th

Book now

Most fusion startups follow one of two paths: magnetic confinement or inertial confinement. The former uses a magnetic field to control the plasma and squeeze it until conditions are reached for nuclei to fuse. The latter approach typically uses a laser to compress the fuel pellets.

On the other hand, common fusions are attempting to use steam-powered pistons to compress fuel-powered fuel. The US Navy attempted something similar in the 1970s, but the general fusion believes that modern computers can solve some of the timing issues that plagued previous attempts. It doesn’t show that it is yet, but states that if completed, LM26 should be able to reach a scientific break-even point.

Now, companies need to raise more funds if they want to prove that their approach is a viable competitor.