The new Netflix film, “The Electric State,” depicts a world full of robots, but as we know it, it’s not a robot.

Brothers Anthony and Joe Russo (previously directed the two Avengers blockbusters, Infinity War and Endgame, on a $320 million budget. It turns out they rebelled against their human masters, lost their war and were exiled to the southwest region, an area where the film’s heroes (played by Millie Bobby Brown and Chris Pratt) must creep up.

Importantly, in the case of Matthew E. Butler, the supervisor of visual effects, these robots are, designably, “deliberately antithesis” of the robots that exist today.

“Most of us have seen modern robots…and we’re used to these designs,” Butler told me. “When you look at Boston’s dynamics robots, it becomes even bigger and bigger when you concentrate the mass of the robot in the center of the robot and come out into the limbs because it’s just a defensive design.”

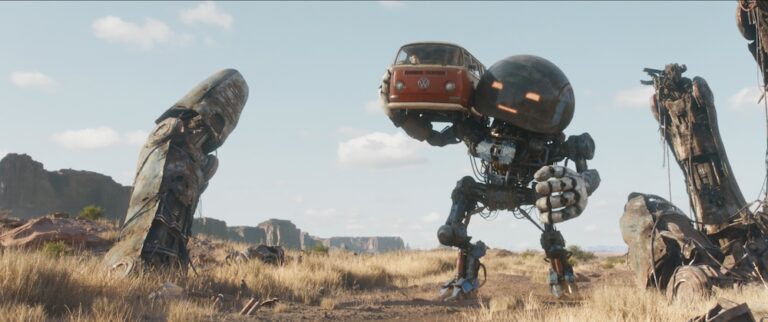

In contrast, the film’s robot cosmos have a “huge head around a small neck,” and Butler is described as “the worst design for a robot.”

Like the film itself, its design is based on an illustrated novel by Simon Stallenhag of the same name. Butler explained that Cosmos and other quirky robots often portrayed from real pop culture have an explanation in the movie. They are made to be “unthreatened.”

All of that had to start with designs that were essentially unrealistic by Butler’s team, but turned it into something that they felt “physically believed and real.” For this reason, they decided to celebrate Cosmo’s original designs with “silhouette fashion.”

“You squint your eyes and move him away from the (camera) camera and he looks like a Cosmo. “But if you go up close and scrutinize your shoulders, you’ll see that there’s a push rod there. You can see the motor, and you can see the same circuit on your ankles and feet.”

The goal is to convince the audience that “thing can really work.” Once they are certain, they embrace the design of the Cosmo and other robots without looking at all the details.

And yes, there are many other robots. Butler said his team must risk “hundreds of unique robots” to their lives. Not because all the robots in this alternative world are unique, he said, “In movies, they usually just introduce individuals.”

In other words, each robot was an individual character. And unfortunately, for the VFX team, there were no easy shortcuts that they had to be as realistic as possible.

“We scratched our heads many times. “How are you doing this?” “If you have 100 different robots and they’re all moving, they have to be able to move. That means you have to be able to rig them, so someone has to design them, someone has to draw them, someone has to animate them.”

To make these robots come true, Butler said the team used a combination of traditional optical motion capture using an accelerator-based suit and a new system. This allowed a troupe of seven motion capture performers to work with live-action actors on location and set, providing the basis for animated robots in which their performances are animated.

Butler emphasized that this process is much more complicated than simply transpose the actor’s movements into the robot body.

“Use the little Herman as an example,” he said. “You have a (motion capture) performer. He’s adding his talent, his performance, and that’s who Chris Pratt can act now. Then you say, “Well, OK, but the actual robot can’t do a lot of things this guy can do.” So you have to change it based on the limitations of the robot itself’s design. ”

And it’s not finished yet: “And you talk to the director, and you now have a certain change in the traits you need to respect, so you change it, and you change it, and you have your great voice actors who add it a lot, and now it’s “Well, well, if you need to change the character (robot), if the character (robot) needs to change,

Ultimately, Butler said that the robots seen on screen were created by works that all artists and performers come together.