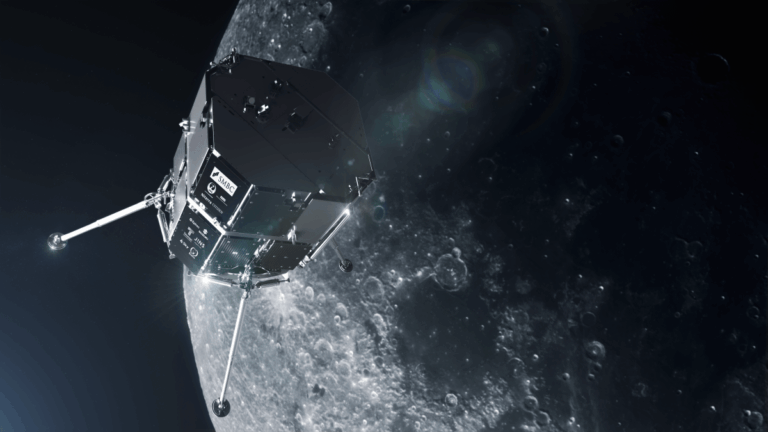

Europe would have just struggled with set-off attempts to reach another milestone in commercial races to use the resources of the moon. Tenalish was set to become the first European-made rover to land on the moon, and was on a lander that lost contact during an attempt to land.

If confirmed, this will be the second failed mission of the Hakuto-r Commercial Lunar Exploration program two years after the previous crash that already crushed hope.

This loss is particularly felt in Japan. The company behind Hakuto-R and the persistent, now missing Resilience Lander, Ispace is a publicly listed Japanese company. But it is also a blow to Europe. The European Space Agency (ESA) supported the mission. The rover was designed, assembled, tested and manufactured by isspace-europe in Luxembourg.

Luxembourg is not just a base in Ispace Europe, but the reason the entity was created in 2017. As part of the Spaceresources.lu initiative, the small country has become the second in the US to adopt legislation that provides businesses with the right to own resources extracted from space.

If tenacious Luxembourg-based operators could drive it on the moon, the Rover would have captured the video and collected the data. One of the tasks was to collect the soil for the moon called Regolith as part of a contract with NASA, which is supposed to transfer ownership of the sample.

“I think this will be extremely useful in terms of both the meaning of commercializing space resources and how to do this on a large scale, and in terms of global participation and coordination,” Ispace-europe-europe CEO Julien Lamamy told TechCrunch, an attempt at Eve on the Landing.

It was also the first time for a European company to win such a contract from NASA. But it took some degree of coax to boast about the ramami for the agile team of 50 from 30 nationalities that created this unique little rover.

Despite his resume, including time at NASA Jet Propulsion Research Institute and MIT, Lamamie is not bragging about it. In our conversation he acknowledged that he needed to “lead his inner American” to explain the achievements of his team. But that’s also because Ispace is intentionally cooperative.

For example, a lightweight scoop aimed at collecting regoliths for NASA was created by Swedish mining equipment provider Epiroc. “We could have done this ourselves. Instead, we found an opportunity to think about space in the ground industry,” Ramamee said. “The more people participate, the better.”

More people are also participating in Luxembourg’s space ecosystem. The Luxembourg Space Agency (LSA) was established in 2018 and the country has actively supported sectors that have become mainstream from niches since the Space Resources Act was adopted.

“It’s better than that, but there are now many companies in the value chain that have been established downstream of iSpace,” Lamamy said. He cited the example of Magna Petra, a startup affiliated with iSpace, a rare resource from the moon, mining helium 3.

“Our ambition is to develop a space sector that is highly integrated with industry on Earth and opens new market opportunities in both space and Earth,” Luxembourg’s Minister of Economy, SMEs, SMEs, SMEs, Energy and Tourism, said in a comment when Ispace-europe announced the completion of its flock.

That ambition is driven by money. Tenaiss was developed in a joint investigation from the LSA through an ESA agreement with the Luximbourg National Space program, Luximpulse. According to a Deloitte study of the Luxembourg space industry, tax incentives or direct AIDS are available to both startups and multinational companies.

Unusual payload

Tenasious was designed to weigh about 5 kilograms and half the weight of NASA’s Sojourner Mars Rover. Lamamy explained that by choosing high-volume, power-efficient components, his team was able to build a very small system that is cheap to manufacture and send to the moon. This has essentially limited the payload, but is designed to reach up to 1 kilogram.

As part of the Resilience Mission, Tenalious’s payload included the scoops needed for a NASA mission, and perhaps unexpectedly a miniature red house. The small sculptures at this small Swedish cottage, known as the Moon House, should be the first home of the Moon, a project pursued by artist Michael Jenberg since 1999.

“It’s not about science or politics, it’s about reminding us that we all share: our humanity, our imagination, and our longing for home. As Carl Sagan once described our fragile planet, red houses staring at the “pale blue dots,” says the Moonhouse site.

The Ramamee team was ready to take charge of bringing Moonhouse to a good location and taking photos, and took the role seriously. As part of the Rover test, operators had rehearsed several times at both the Luxembourg test sites and several European locations, including the Canary Islands in Spain.

Poetic, this may have seemed less priority to NASA, but it may not have been for Lamamie. “It’s an interesting paradigm shift. Yes, I go to the moon to improve my knowledge of the moon from a scientific and commercial perspective, but now I have access to artists, entrepreneurs and educators.

Unfortunately, this probably needs to wait.