The Federal Reserve is stabilizing interest rates as it navigates the uncertainty kicked by the president who continues to pressure the central bank to lower them.

It’s a cynical, whip-inducing reversal for Fed policymakers who were on the verge of a rare feat a few months ago. Get ready to take away the driving forces of historic inflation and reduce borrowing costs without causing massive layoffs known as “soft landings.” But President Donald Trump’s rapid uptake of global trade has pushed the Fed and its leaders into difficult positions. They feel that the approach they are waiting for is their best strategy for now may be their best strategy.

“The Fed has fallen into a near-impossible situation where the two orders are likely to move in opposite directions,” said Sheemasher, chief global strategist at Principal Asset Management, referring to the Fed’s dual mission to keep jobs high and keep inflation low.

“But government policies — incredibly uncertain in themselves — will determine both the timing and magnitude of those movements,” she wrote in a note to her client on Wednesday.

The concern is that the Fed will force the Fed to cut interest rates to cause unemployment, as the economy damaged by tariffs risks causing higher inflation. After peaking above 9% in mid-2022, annual inflation has hovered for nearly a year just north of the central bank’s 2% target.

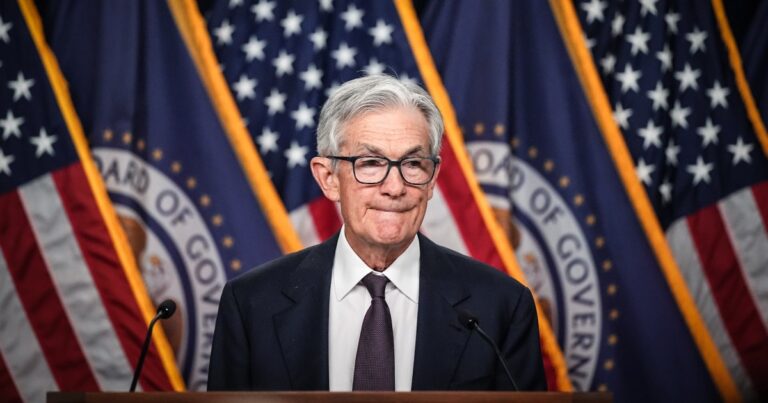

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said Wednesday that holding Putt at interest rates would allow the Fed to “wait and see” how the economy unfolds. However, policymakers updated their concerns about “stagflation” by warning in a statement Wednesday that “high risk of unemployment and increased inflation.”

“The tariff shock reduces actual GDP growth, while simultaneously increasing prices, putting the Fed at the corner of the dilemma,” warned Brian Callton, chief economist at Fitch Rating, in a note Wednesday afternoon. “The policy movements needed to maintain full employment are the opposite of what is needed to curb inflation. Moving one policy lever to achieve two conflicting goals is problematic.”

Politics is becoming more difficult, and the Fed’s decision is likely to elicit Trump’s rage. Trump has repeatedly beaten Powell, whom he appointed in 2018, breaking long-standing norms on political influence on monetary policy by escalating his attacks in recent weeks.

“Cut your interest rates, Jerome, and stop doing politics!” he wrote about Truth Social on April 4th. Two weeks later, he again called Powell “too late” and said, “The ending can’t come quickly enough!” In yet another post a week later, Trump called Powell the “major loser.”

Powell told reporters Wednesday that Trump’s comments had no impact.

“That doesn’t affect either our work or our way of doing things,” he said, adding that both of them also called for a meeting with Trump and demanded that the president. President Joe Biden re-appointed Powell in 2022, and despite a recent barrage of criticism, Trump told NBC News’ Kristen Welker last week that he would not try to eliminate him before his term ends in May 2026.

“Why am I doing that? I can replace that person in another short period of time,” he said.

The challenges in recent months mark the second time Powell weighed the ways in which he handled economic fallout from Trump’s trade policy. In 2019, Trump was similarly threatening China’s higher obligations. Faced with a similar jab from Trump, Powell cut interest rates three times through a barrage of Twitter posts at the time, easing the US economy preemptively from a higher obligation blow.

Powell signaled on Wednesday that this time it was different. The Fed was not worried about the impact of lower rates inflation as prices were rising slowly in 2019 at a slower pace than they are now. Core consumer spending, a measure of inflation preferred by the Fed, showed that prices rose at 2.6% per year in March, while the same scale was recorded at 2% below 2% in 2019.

“This is not a situation where we can take the lead, because we don’t really know what the correct response to the data is until more data is displayed,” Powell said.

The market expects the Fed to cut interest rates three times by the end of the year, but some analysts aren’t that sure. “If the basic cases of stable labor markets and rising inflation are correct, we will not see a path to reductions in 2025,” a researcher at Bank of America said on Wednesday.

In the meantime, Powell avoided commitment to future moves, given the widespread uncertainty that Trump’s tariffs are for corporate bosses, small business owners and consumers.

“It may be appropriate for us to cut fees this year, and we may not,” he told reporters Wednesday. “I don’t know.”